Sit through a few commercial breaks during a football game, or leaf through the pages of an automotive magazine, and you'll see them: an ever-changing parade of shampoos, conditioners, gels and such, all promising a flake-free scalp. While preferences for beards and clothing change every generation (or sooner), a man's desire for a full, healthy head of hair remains the same. So, although the money spent by men on cosmetics pales in comparison to the female market, male grooming is a growing business, reaching $166 billion worldwide in 2022 according to a report by CNBC. These products, and especially the advertisements that promote them, are so much a part of everyday life that it is easy think they have been with us forever. Indeed, the dry scalp condition known scientifically as pityriasis capitis is as old as humanity itself. Yet the American male obsession with dead skin cells is less than century old and is the invention of a single man: Daniel Druff.

Like most self-made men, Druff's work ethic and business acumen were developed during a challenging adolescence. He was born in Chicago in 1890 to Samuel Druff, a Scottish immigrant who worked as a cabinet maker, and Louisa Jenkins, the daughter of a schoolmaster. In 1904 Samuel died, leaving Louisa to care for Daniel and his younger sister Agatha. The family bounced between towns in northern Illinois and southern Wisconsin as Louisa struggled to find stable employment as an English teacher at various girls boarding schools. Druff, forbidden to stay with his mother and sister during the school year, would return to Chicago to work for his uncles in the cabinet shop, only reuniting with his mother during the summer. However, Louisa made sure that Druff kept up with his lessons; in later life he was often known to quote Horace or Shakespeare during tense moments in board meetings. But by the age of thirty-one Druff grew tired of working for his overbearing uncles and set off by train for Los Angeles, seldom to return to his family in Chicago, even after he became a millionaire.

Evidently, Druff had no plan upon arriving in southern California except to work as a carpenter building sets for Hollywood's fast growing studios. It proved a good bet — his first among many — as he soon joined the construction crew for the Douglas Fairbanks 1922 silent film Robin Hood. The production involved massive recreations of medieval England, including sets designed by the architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Thus, Druff would have been assured a comfortable living as a finish carpenter during Hollywood's golden age had not destiny entered the story. The studio's makeup artist was George Westmore, an Englishman sought after as a hairdresser by Winston Churchill before moving to Hollywood and becoming involved in cinema. One day late in the production, Druff was taking an empty handcart away from the set as Westmore arrived with a large crate of makeup and hair products for the cast. The imperious Englishman demanded the use of the handcart, and Druff begrudgingly agreed to wheel the cosmetics for Westmore. What started as an awkward chance encounter soon turned into a business relationship. With carpentry work on Robin Hood nearing completion, Druff became Westmore's delivery driver, collecting products from various LA apothecaries in the morning and bringing them to the set. By 1924 and the release of The Thief of Bagdad, Druff had become the makeup acquisition manager for the entire Fairbanks Picture Company, a very far cry from the old Chicago cabinet shop.

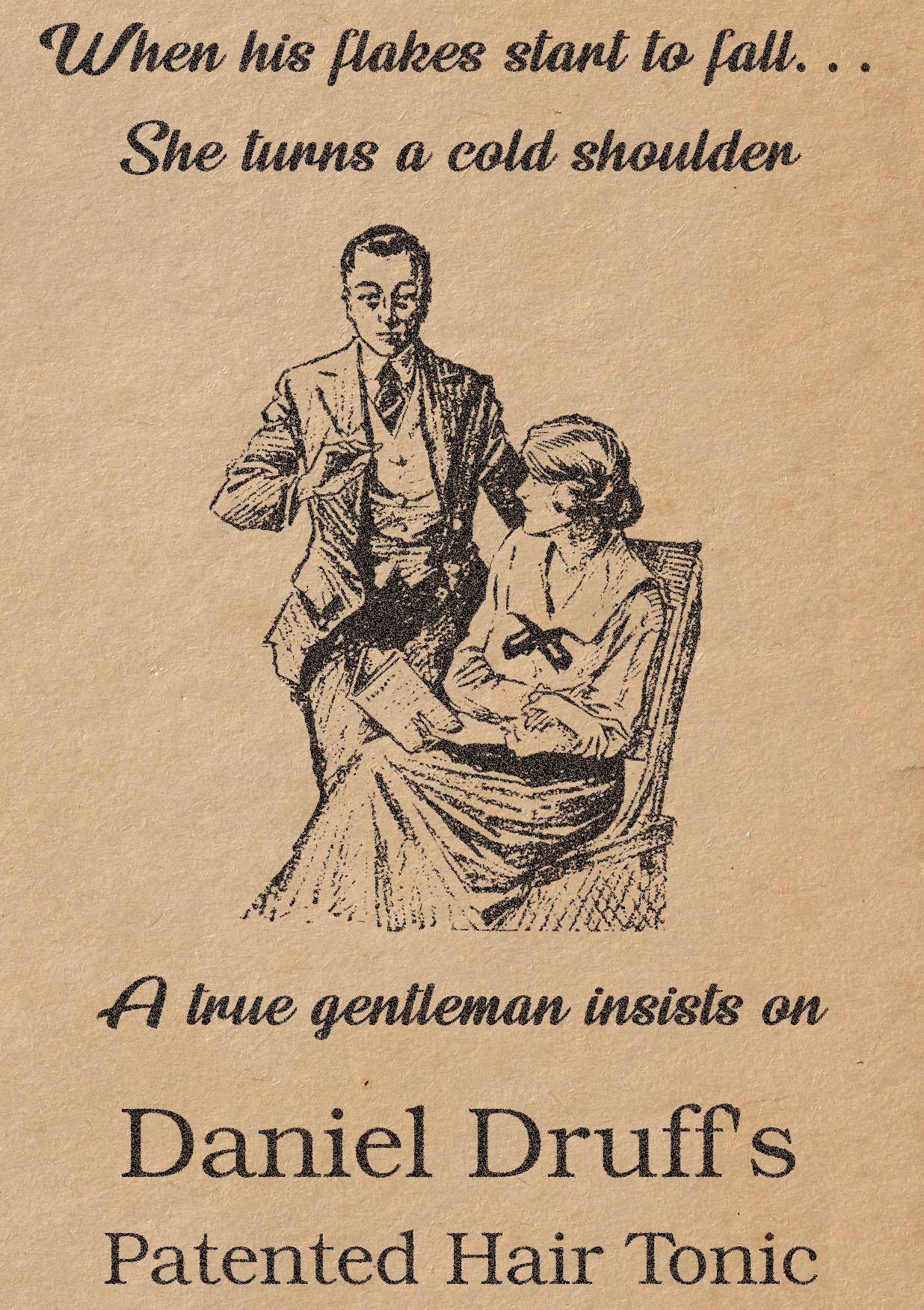

It is difficult to overstate how fundamentally the birth of film changed the way everyday Americans thought about their appearance. In the 1800s, photography had made famous figures like Abraham Lincoln and Mark Twain recognizable to the masses, but moving pictures brought actors to life. Virtually everything that we now associate with glamour, a hyperrealistic beauty, can be traced to the silent film era. Everyday imperfections such as a flaky scalp didn't exist on the silver screen, and the public demanded products that made them look like Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford. Druff quickly outgrew his role at the film company, seeing the emergence of a massive new consumer market before almost anyone else. In 1925 he founded the Druff Pharmaceutical Corporation. It was a clever venture, presenting cosmetics as something akin to medicine: Daniel Druff's Patented Hair Tonic. Druff had a craftsman's keen eye, not to mention a sharp wit. The company's market share exploded through printed advertising.

Having capitalized on film, Druff soon harnessed another powerful medium and invaded the American living room. Radio began as a hobby for engineers and aspiring inventors, but rapid technological advancements soon made it a practical, and potentially profitable, means to address millions of listeners. In his book The Attention Merchants, Tim Wu chronicles the idealistic early days of radio, when it was believed that the new medium could improve the lives of individuals and entire nations with quality cultural and public affairs programming. Advertisers, however, were quick to follow. Today most of us take for granted that in exchange for free entertainment and information, we will be encouraged to purchase many products and services throughout the day, even as we sit in the supposed privacy of our home. In the 1920s, this was a new idea. Druff understood that his product could become a literal household name. While most radio advertising was directed toward women (hence the soap opera), Druff marketed to men who listened in with their families after work. It was a massive success, and by 1928 Druff's Tonic was the leading hair oil in the United States. Even after the Crash of 1929, the company held on to its market share. The obsession with a flaky scalp had gained too strong a hold on the American male imagination.

But even the most robust hairline must eventually recede. Druff was a victim of his own success and boundless ambition. His hair tonic sold so well that it became synonymous with a dry scalp, so that to ''have Dan Druff's'' became the modern byword for the condition: dandruff. The fatal flaw was the tonic's scent, described as a ''proprietary blend of fresh alpine herbs''. The scent immediately identified the user as someone with a hygiene problem. For once, Druff reacted too slowly. By the time he introduced an unscented tonic in 1937, a new generation of men, coming of age during the Great Depression, began to resent their fathers' reckless pursuit of wealth and the concomitant excessive grooming. Druff's Hair Tonic became an old man's product, and the company struggled to survive as niche product through the early forties. In 1948 Druff's was acquired by a large conglomerate. After years of poor sales, the brand was discontinued in 1953.

Yet the end of the Druff Pharmaceutical Company wasn't the end of Daniel Druff. He worked as an independent advertising consultant for another decade until his retirement. Druff died in 1966, survived by two ex-wives and five children. Although he is largely forgotten outside of the cosmetic and advertising industries, he achieved a kind of immortality through dandruff, the condition that bears his name and continues to generate billions in sales every year. Surely he would be amused that his former competitors, such as Proctor & Gamble, now pay fortunes to mention his name as they sell their products during the Super Bowl.